The History of Eudora, Kansas

The History of Eudora, Kansas

Site Content

Frontier Challenges

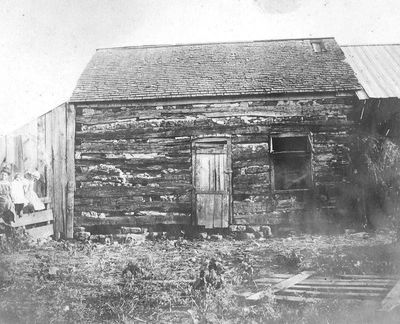

Photograph to right: Schneider log cabin on E. 7th Street, northwest of city cemetery

Of the many dangers early settlers faced, disease was ever present. Malaria, cholera, and dysentery were but a few of the diseases feared by settlers. Haywood Marley, who settled on his farm two miles east of Eudora in 1870 with wife, six children, and sister-in-law in 1870, buried his wife, sister-in-law, and two children who had died of illness within two years of arriving. “His endurance was sorely tried by sickness, poverty, and distress in the new country, but much was alleviated by the help of the kind Quakers and newly made friends,” stated his obituary.

An Indian fort built like a corn crib with slots for long guns, said Mary Moody, Eudora resident, stood behind 712 Main Street in the alley, a testimony to resident’s fear of border ruffians and other predators. [Note: The communal first log house of the German settlers also was said to be in this alley, a few storefronts north of the fort, Moody remembered.] Although the Indians and settlers seemed to have friendly relations, problems could arise such as when an Indian woman took the youngest sister of H. W. Hagen who lived in Eudora before the Civil War in a home south of the Wakarusa Bridge on the east side of the road. The child was returned to the family several hours later, according to Hagen who told the story to Will Stadler when visiting Eudora 50 years later.

The winters of the 1850s caused temperatures to drop below a minus 20 degrees Fahrenheit and two-foot snow falls. Summer strong winds stirred up heavy clouds of dust formed from prairie grass burning and soil tilling. Wrote G.W. Brown in the Herald of Freedom April 14, 1855: “We are frank to confess that we have felt more inconvenience from the wind and dust, since our arrival in Kansas, than from any other sources.”

Drought also dashed crops and high hopes. After surviving the severe droughts of 1854 and 1855, settlers endured the drought of 1859, which destroyed much of the crops throughout Kansas and left the territory in an even greater economic depression. Most crops failed in 1859 and 1860, according to several accounts of the time. Prairie grass that usually produced tons of good hay stood only two inches high before it dried to a crisp. Starting June 19, 1859, not a shower of rain and little snowfall occurred for 16 months. The ground was dry as ashes, wrote Richard Cordley.

A grasshopper invasion, too, may have caused new Eudora settlers to think of moving elsewhere. Wrote Sister Julia Gilmore, who taught at the Catholic school in Come North! The Life Story of Mother Xavier Ross, Valiant Pioneer and Foundress of the Sisters of Charity of Leavenworth (New York City: McMullen Books, 1951): “One Friday in August was a little hotter than the preceding days. By noon, Mother Xavier and the Sisters noticed that a cloud seemed to be rising in the sky; not a glorious black thunder cloud that would mean cool wind and sharp lightning and a longed-for shower of rain. This yellow gray cloud had no deeper nor shallower tints to it, rising steadily, moved swiftly, shutting off the noonday glare. The few chickens in the yard mistook the cloud and went to roost. Then came a sound, deep, ominous, not wind, not thunder. It has a rasping edge, a rumble unlike anything before heard. The cloud could be seen sweeping across the land, not high in the air but beclouding the landscape like a black fog. Only this was dry and carried no cool breeze with it. Roaring with the whir of grating wings, countless millions of grasshoppers filled the earth below and the air below.

“Every person available helped shoo off the grasshopper with brooms, branches, or stick, but it was hopeless. In the convent yard, not a week or stubble was left because of the monster. For three days, the Sisters watched this devastation continue; then they saw the pest, still hungry, rise and pass to the southeast leaving behind it only a honey-combed soil where eggs were deposited for future hatching and a famine-breeding desolation.”

The grasshoppers stripped leaves from trees and ate clothes hanging on clotheslines, Sister Julia wrote. The only harvest was food that grew under ground such as potatoes, beets, carrots, and turnips.

Thomas Harris, who moved to this area from Indiana and bought three 40-acre tracts near Hesper, said in a 1935 news article that the grasshoppers ate the wheat down to the ground for 10 straight days. On the 11th day, the wheat didn’t appear again. People burned the grasshoppers’ eggs. By July, nearly all the grasshoppers were gone, Harris said. He planted a corn crop that survived and ate biscuits for breakfast, corn bread for dinner, and mush for supper during these hard times. The grasshoppers would return in 1893 and 1913, but not with their earlier devastation.

Will Stadler, editor of the Eudora newspaper, wrote about the hardships. “The stories told to me by my gentle mother of privation and hardships, grasshoppers, droughts, storms and floods, courage and fortitude — and an indomitable will of the hardy few to conquer the soil and make for themselves a home in Eudora, were pitiful to say the least. She told of the tallow dipped candle light, cornbread made with salt and water, parched wheat as a coffee substitute, of the victories over nature — of loyalties to ideals and of the getting together, for the few simple pleasures that gladdened those drab, dreary days of the early life in Eudora.”

Lack of housing, too, added to the burden of daily life. Elizabeth (Cole) Conger, arrived in Hesper at the age of 35 in 1855 (or 1858) with her husband John and four children. They brought stock from the dry goods store they had owned in Rochester, New York. The Congers lived with another family in a one-room house that was 10 feet by 12 feet.

Food supply on the frontier also could be in short supply. So low was available food that the Eudora Township Relief Committee organized December 1, 1860 with W. A. Dinsmoor, W. H. Shreve, and A. A. Woodhull at Woodhull’s office. They stored goods hauled from Leavenworth and Atchison in Julius Karnasch’s cellar. Family surnames within the city receiving assistance in June 1861 were Basemann, Bohnet, Rupple, Fox, Keleker, Hoppenau, Lavo, Weber, and Zeisenis. Those getting assistance who lived outside the city were Bartheldes; Legget, J.; Legget, W.; Benton; Mayer; Pinnick; Cone; Reel; Daniels, G.; Rote, S.; Richards; Doniphan; Scheiswald; Graham; Sears; Haelsig; Stratton; Suerig; Huber; Switzer; Huneke [Heinecke]; Thoren; Jennings; Verch; Jones; Vogel; Joy; Waley; Kane; Wallace; Largin, P.; Wilson; Winger; and Legget, G.

Prejudice was another possible challenge. Heinrich Balduin Möllhausen, who wrote of traveling through Kansas in the 1850, said: “The prejudices of Americans against everything originating in Germany have in some respects diminished considerably. For even though, for example, the wearing of a mustache was, as I remember quite well, taboo among native Americans a few years ago, just as beer drinking was considered ridiculous, one now notices beards even in the Eastern states and among all classes of society; beards which would do honor to a German demagogue and make a pampered ensign proud.” However, German origin might have been beneficial as it caused the German settlers to band together, and nearby Lawrence also had a relatively large population of Germans.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.